How to study 101

How not to study

I was always considered a "gifted" or "smart" kid. Still am in a lot of instances. But I like to make a distinction between being smart and having the ability to process information quickly. One can definitely cancel the other one out. Because I could process information quickly, I never had to study as a kid. I purposefully took shortcuts, which definitely wasn't smart, and it lead me to a point where the sheer amount of information was so much, that my shortcuts didn't do their tricks anymore. No more studying the night before my exam and getting off with a 5,5. Not at university at least. This lead to my inevitable drop out in 2022, but now it's 2023 and I'm back at university. But these days I tend to ace my exams. But how do I manage to do that?

There's a very clear reason why I failed my first year at university. First things foremost, I'm a law student. Law school is not difficult, it's just a lot. And mainly things you've never learned or heard before. Because that was one of my shortcuts: Everything I had to learn for exams up until that point was always either something I'd learned or read somewhere before, or it was logically deducible. No need to study much. But for law school I had to learn to use certain articles and I had to learn systems that were in part built on centuries of (not always logically put together) traditions. Hence my shortcuts not working. My main problems consisted mostly of two things: Firstly underestimating the workload and secondly realising the extent of my problems too late.

I like to make the following comparison between studying, my brain and information. In the end there's one clear goal when it comes to studying: You want to be able to recall information on a certain topic under various circumstances (like when you've got an exam, but in my case also when someone asks me for legal advice). I like to compare it to your brain being a busy shopping centre and all the information is stored in different shops in different departments. Say you need a pair of black jeans from the Pull and Bear. If it's your first time shopping at this place, it'll take you longer to find it as opposed to the case in which you've shopped there plenty of times. In the latter case you'll know exactly where the Pull and Bear is, what the fastest way to get there is and where they keep the black jeans in the shop. But what does this have to do with studying? Studying is simply an elevated term for when you're putting genuine effort into learning something properly. To a certain extent you've learned to find your way around certain places (like where you grew up), so if you see your brain as a place, this prompts the notion of learning your way around your brain space. I'm not suggesting everyone should go full Sherlock Holmes and name their brains their "mind palaces," but looking at your mind in this way has helped me out a lot. Because if you go to the jeans section of Pull and Bear enough times from various starting points, at some point you're reaaaally gonna get the hang of being the quickest Pull and Bear-jeans-buyer.

The main thing that's made a difference in my approach to studying and just learning anything new in general is the combination of the following two methods: Active recall and spaced repetition. In this article I will first cover active recall, then spaced repetition, and to conclude I'll reflect on how the methods have, or have not, benefitted me in my education.

Active recall

Active recall is the concept of finding ways in which you actively stimulate your brain to recall certain information. If you're learning something for the first time i.e. it's your first time at this store in the shopping centre, it might take you a while to find what you're looking for. Say you're looking at a map and it tells you to go downstairs and take a left turn. Now that information is in your head, you know how to get to the place. But will you remember these instructions after you've left the map? Research has shown that passively processing information is a far more inferior way of learning new information compared to actively processing it. But what does it even mean to actively process or recall things? It means that instead of passively reading, listening or copying information in your summaries, you actually do something with it. Examples of what this "doing something" can look like are:

- Doing practise exams;

- Making your own practise questions;

- Making flashcards

- Quizzing your friends, but also the other way around;

- Teach your teddy-method: Explain complicated concepts to your teddybear;

- Explaining things to friends who don't study the same subject. This leads to them asking questions and in answering those you're also actively recalling information whilst simultaneously looking at things from another angle. This last thing also adds another dimension to your knowledge on the topic;

- Summarise things after you've read them, without looking at the text (unless you really don't know something. Then go over the text again and summarise after that);

- Reading text using the SQ3R-method.

Of course there are countless other ways to incorporate active recall in your study system, and some may work better for certain people than others, but that's what things like Google, trial and error are for.

Spaced repetition

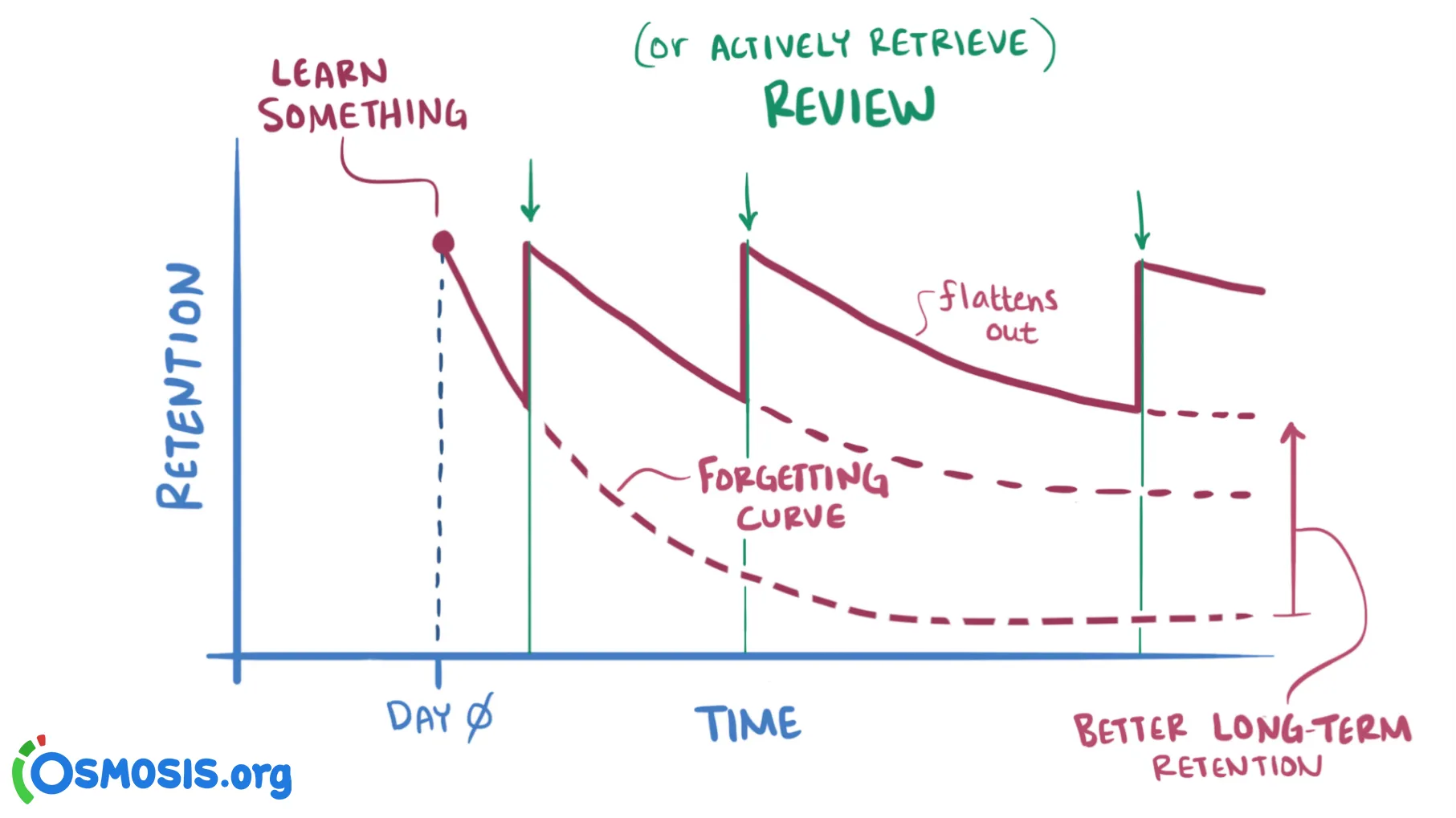

Spaced repetition is the act of repeatedly recalling information over spaced amount of time. To go back to the shopping centre example: Spaced repetition would be to visit Pull and Bear's jeans section a few times a month. This is because there's a difference between short term memory and long term memory. When you first learn something, your brain puts it in the short term memory, which renews every now and then. If you want to keep the information in your long term memory, repetition is the key to that. Say you want to learn the planets of our solar system. You learn them once maybe right before a test, then you pass that test and you're done. But after that you won't keep remembering the planets. The more time passes, the more the memory of the information will fade until you won't be able to recall it properly. This is what we call "the forgetting curve." The more you repeatedly recall the information, the less steep the curve will become. Down below is a graph which illustrates this:

A way to incorporate spaced repetition into your study routine could be keeping practise questions or flashcards on your phone or just in your pocket and going over them every other day before or after school or if you're waiting on the bus or something. You don't need to do every subject every day. For example: When I had European Law (EL) and Administrative Law (AL), I did my EL-questions every Monday, Thursday and Sunday, and my AL-questions every Tuesday, Friday and Saturday. It doesn't have to be enormously extensive, just a quick recap of the main things + the things you struggle with would suffice. It's just about testing how good you are at actively recalling the information at different times.

How these things have made my life much easier

Active recall and spaced repetition cost time. So to start doing it a week before the exam is sort of pointless. I only started actually doing these things halfway through the last semester of my first year at university. They definitely worked to an extent, but I was simply too far behind. My second attempt at law school was amazing however. I aced all my classes without all that much effort, purely because of these methods. That in combination with knowing your brain very well (or hanging out at the shopping centre a lot) made life so much easier. But there's definitely a slight learning curve, especially if you've spent your entire life learning things a certain way. To introduce this new wat of studying to your routine does require careful planning from beforehand. I start every semester creating an outline of what the year's gonna look like for me, when I've got exams and what those exams will look like (open questions, multiple choice questions, presentation etc.). That way I know what I'll need to learn, when and how I'll be doing that. Even if it's just in broad terms, it helps a ton. And whilst active recall and spaced repetition cost more energy than just pushing as much information in your short term memory as humanly possible, it definitely costs much less energy if we're looking at the bigger picture.

Omg you read the whole thing

Or maybe you didn't. However, you at least scrolled to the end and I appreciate that too. Thanks so much for clicking on the post, and if you'd like to receive updates about the site and leave comments down here, you can hit the subscribe-button in the right corner to quickly set up an account. This is already my tenth post on here, and whilst I haven't published much the last few months, I'm still proud as hell of this post. Of this whole website really. And again, so grateful you're reading. I hope you have a great rest of your day and good luck with studying!

References

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborate studying with concept mapping. Science, 331 (6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Butler, A. C. (2010). Repeated testing produces superior transfer of learning relative to repeated studying. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(5), 1118–1133. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019902

Comments ()